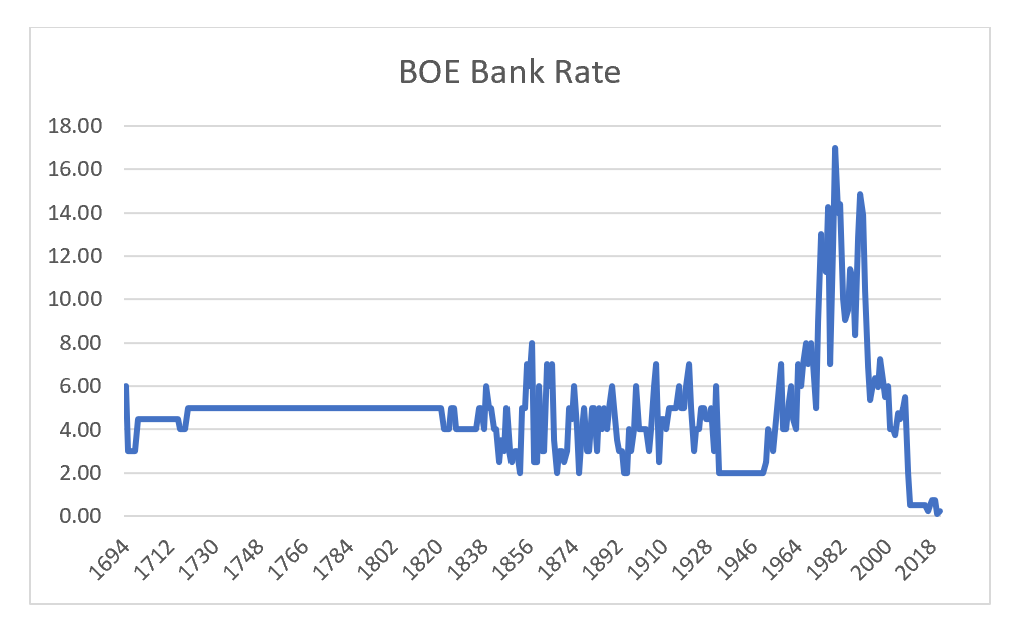

There are many reasons given for why interest rates have been so low. In my posts, I have been coming more and more to the idea that if wages are not rising, then it is very difficult to have inflation. That is wages drive inflation, and the relative power of “labour” then determines inflation rates. Thinking about inflation this way has some benefits. It easily explains the post World War II inflation, as governments set policies to target full employment and rising wages, and also explains falling inflation, as labour markets were opened up to global competition. It also helps to explain how the last 60 years has seen the Bank of England set both the highest and lowest interest rates in its 300 plus years of setting interest rates.

Can we quantify labour competition? And if so, would it gives us a guide to where inflation might be going? Japan was the first market to suffer from deflation, and very low bond yields, so is a good candidate to look at first. Using the IMF Wage Tracker, we can see that Japanese wages began to inflect lower in the early 1990s.

After the Plaza accord of 1985, the Yen doubled in value against the dollar. This meant in USD terms, GDP per capita rose significantly. This put Japan at a significant disadvantage against then competitors South Korea and Malaysia, a disadvantage that was compounded by the currency devaluations of the Asian Financial Crisis. The problem for Japan workers was then further compounded by the entry of China to WTO in 2001. Given the relative population size of China, this would have had an even more negative effect on wages than the Asian Financial Crisis. Looking at below graph, and the rising GDP per capita of Korea, as well as Chinese GDP passing Malaysian levels, it is hard not to believe that the worst of the deflationary pressure on wages has passed by.

We can look at the EU and North America to gauge at what levels of income do low cost manufactures stop exerting wage deflation pressure in advance economies. The EU provides a good test case. Spain was a low cost manufacturing destination when it first joined the EU in 1986, and Poland is now a low cost manufacturing destination after joining the EU in 2004. Given freedom of movement, I would suggest labour deflation pressure in Europe are more intense in the short term, but can adjust quicker than Japan due to internal migration. Spain joining the EU seemed to put intense pressure on German wages, but Poland joining the EU seems to have affected Spain far more than Poland. Given the unlikelihood of any other nation joining the EU, it would seem that the worst of the deflationary labour pressures are over.

Mexico joined NAFTA in 1993, which should have put pressure on wages in the US. Compared to Japan and China, the relative populations would suggest much less wage pressure. Also without the free movement of labour that underpins the EU, you would expect the adjustment to be much milder. In GDP per capita terms, its hard to see any influence of NAFTA on the US. Even more intriguing is that Mexico GDP is flatlining around USD 10,000 for the last decade, with seemingly no negative effect on US GDP per capita.

To me it looks like wage competition in Japan and Europe are coming to an end. This is making the chances of rising wages and GDP in Europe and Japan much more likely in my view, after 30 years of stagnation in Japan and 10 years of stagnation in Europe.

It seems to me that in 1970s and 1980s politics and trade combined to create an environment that sought to weaken “labour” which has continued to this day. Both Europe and Japan had to make much bigger adjustments to collapse of socialism, given much closer trade links to Eastern Europe and China. From a trade perspective, the rising wages in outsourcing nations suggest the worst is behind us for labour deflation. The tendency towards nationalist and populist policy making suggest politics is also changing. Rising wages and inflation looks likely to me.