I had always marvelled at the awesome ability for the market to mete out justice. Japanese property bubble I experiences first hand when I was 17, and over the subsequent years saw the Japanese deflation take hold of the Japanese economy. I spent 1998 in HK as the Asian Financial Crisis took hold. My first job out of university was with UBS, about a month before the peak in the dot com bubble. Within 6 months of joining half the people on the floor had been let go. One of my graduate friends joined Enron in 2000 - and I had just read a glowing article in the Economist about how Enron was transforming the energy market in the US. I was jealous that she was joining such a cool company.

One year later everything had changed. When we met up again, I asked her if she had any idea Enron was in trouble. She said to me that her area never made any money, they just assumed everywhere else was doing great. Enron’s reported numbers are still on Bloomberg, and don’t particularly scream fraud, although how they grew revenue from USD 13bn in 1996 to USD 100bn in 2000 should have raised some red flags. Chanos built a very successful career and business on the back of discovering the Enron fraud.

But Chanos is hanging up his short selling shooters. There are two reasons in my view. Fund management is about two different things - making money and raising money. To make money in short selling you really want to see bankruptcy. Bear markets are ok, but you really only make a small amount of money relative to the risks you are taking. Bankruptcy, on the other hand, means your short will not only be super profitable, there is very little chance it will rally either. We can get quarterly bankruptcy US Chapter 11 filings back to 1995. We know there were a number of bankruptcies during the 1970s and in the early 1990s, so we can see that initial jobless claims and bankruptcies are closely linked in the US. That is shorting in the US for the last 10 years has been very difficult.

The second reason is that you need demand for short selling. In both the dot com bust and in the GFC, the largest stock and the index fell significantly. This means that allocators that hedged or had allocations to short selling will outperform, and raise money, which will naturally lead to money feeding back to short selling funds. The 2022 bear market, would have helped short sellers for a little while, but with the Magnificent seven and tech doing so well in 2023, demand for short selling would be muted at best. “Buy the dippers” have won again.

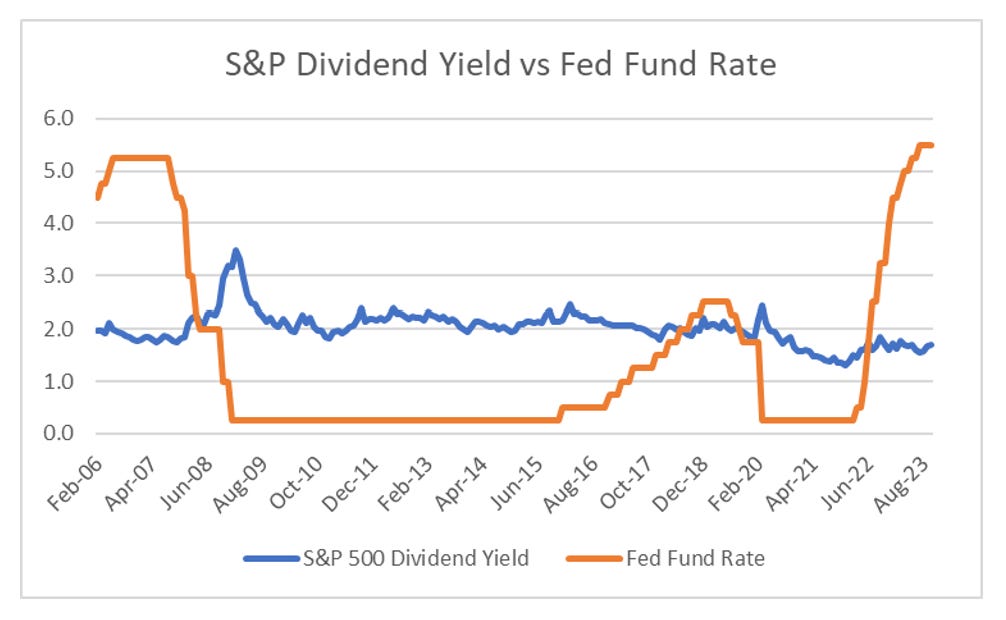

So its easy to see why Chanos is closing down - hard to make money, and hard to raise money. Does this mean that short selling is a dead industry? This is an important question for me - as I am thinking of getting back into it. First of all, we should recognise that carry is now positive on short selling for the first time in a long time.

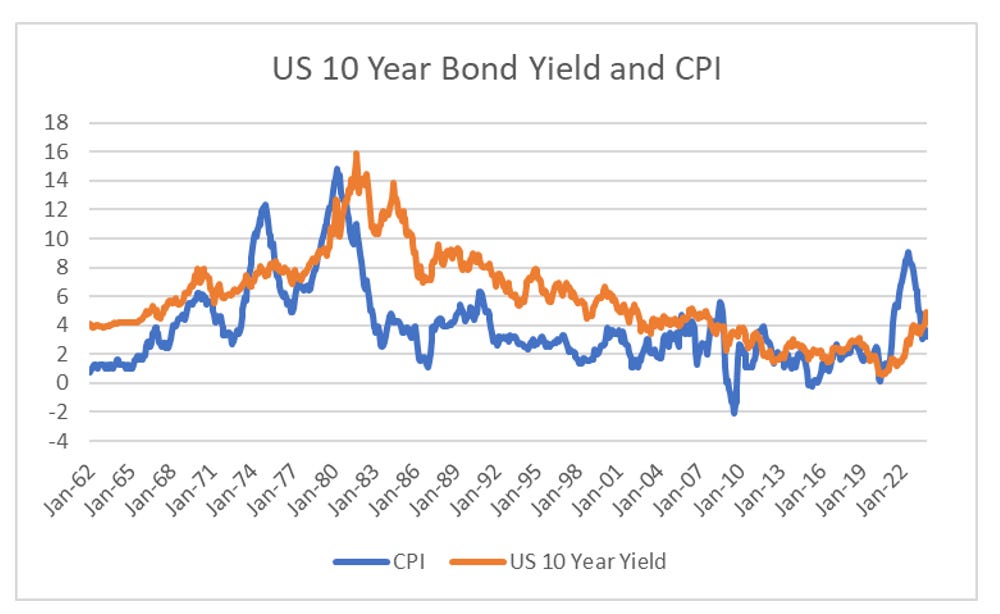

Politically, I think we are entering a new era, where governments are willing to do whatever it takes to raise wages and have full unemployment, which is in marked contrast to the what we saw 1980s onwards. So we need to lookback at the post World War II period to see if short selling could work. From 1950s to 1980s, producer and consumer prices moved together, although the 1970s was marked by government mandated price controls. You can see in this period, the CPI of eating at home or eating out, moved close to one for one. This was an era of cost push inflation - or rising wages driving inflation.

From 1980 onwards, voters (and subsequently governments) accepted higher unemployment and bankruptcy as the price to pay for lower inflation and interest rates. That is the political and business elite accepted the possibility of foreign competition, bankruptcy and default as the cost of lower interest rates and lower inflation. What I am trying to say, is that Chanos and other short sellers like Paulson, or Michael Bury are easy to portray as outsiders fighting a system, that was not the case. This era also reflected an era where economic adjustment fell on workers more than business. An era of profit driven inflation.

It is easy to see in economic data that both CPI and bond yields were kept low from 1980s onwards. Bankruptcy and unemployment was policy, and this is what short sellers thrive on. What we need to work out is whether governments will try and supress profit driven inflation to allow wage inflation to continue? Are we going back to 1950s and 60s policy?

Governments are reducing the power of markets to keep wages low. Tariffs is now seen as an acceptable policy choice. So are capital controls, and reducing the scope of immigration to keep wages down. But taking a closer look at markets, I can see a role for short selling, that works within the political system we are moving to. Rapidly rising minimum wages, progressive taxation, trust busting and higher interest rates are all part of this mix. Areas where governments can directly control price increases are probably areas to look at. Utilities is one area. REITS could be another. Relative to shorting Enron, this is pretty unexciting stuff.

So why did Chanos fail? Governments have moved away from bankruptcy and deflationary policy. The endless economic crisis of the 1980s onwards are largely over (1982 Mexican Devaluation, 1991 Savings and Loans Crisis, 1993 Japan crisis, 1998 Asian Financial Crisis, 1999 Argentinian Crisis, 2000 Dot-Com Crisis, 2007 GFC, 2011 Euro-crisis, 2015 Emerging Market Crisis). Without crisis, Chanos style short selling is largely pointless. Does this make short selling pointless? No. But rather than generating huge returns in short periods of time, it becomes cash + plus type product - somewhere in the 10% return range - but in a potentially sideways moving market that could be attractive. But for a short seller who got Enron right, that would be pretty unattractive I suspect.