In recent posts, I have come to the conclusion that rising energy prices are the only thing that can break US markets (absent political change to break cartels - which probably needs higher energy prices to generate the political will for change). To be fair, one of the biggest surprises of the last eighteen months or so is how weak energy prices have been despite the Russian invasion of Ukraine. My working assumption was that energy supplies would be disrupted, and this disruption would get worse over time as sanctions bit. However after the initial spike to USD 140 a barrel, it has settled this year at around USD 80 - pretty much in line with where it was before the invasion.

As I was contemplating this, Doomberg, published a note pretty much saying cheap energy is here to stay.

I am not going to say that Doomberg is wrong here, as I suspect they are arguing from a geological point of view, i.e. that there is plenty of oil out there so prices will always be reasonable. From a geological point of view, I would agree. But market structure is beginning to change, and that can lead to much higher prices. A good example of changing market structure leasing to higher prices is iron ore. Through the 1980s and 1990s, the Japanese were the biggest buyer of iron ore. The Japanese steel buyers bought as one single cartel, and Japan funded every single iron ore mine they could find (through Mitsubishi and other trading houses). This combination of many mines, and a single buyer meant that iron ore stayed at USD 20 a tonne for 20 years. But in the early 2000s, BHP and Rio Tinto began consolidation the iron ore industry, and then Chinese steel makers suddenly became big buyers, and the sellers of iron ore were consolidated and there were many buyers. The iron ore price has stayed well supported at US 100 or higher almost ever since. Even with recent disappointing Chinese growth, iron ore prices have done well.

The rise of the US shale industry has seen a number of new entrants, and looking at US production data, we can see we have hit a new all time high. Since August, the US has added 1 million barrels a day of oil production, no doubt adding downward pressure to oil prices. This adds weight to Doomberg’s view of oil prices staying affordable going forward.

However, the EIA provides leading data (it estimates number of new wells about to be started in shale region) on oil production, and this leap in oil production from the DOE took me by surprise. The EIA data was suggestive of a slowdown in oil production growth, not an increase.

Even weirder is that drilling activity has been slowing for a while in shale region.

So where did this surge in oil production come from? Going through the DOE production numbers, there is one area that is not shale that has seen an increase in oil production - the Gulf of Mexico. Increase is probably not quite the right word, but a return to peak production.

Its been a long time since I looked at US offshore production - but thankfully Baker Hughes still provides good data on drilling activity in this region. As you would expect, shale has been a disaster for the US offshore drilling industry. From this perspective its hard to see how offshore can pull off anymore production surprises.

So offshore growth, for what it is worth is done. Lets take a closer look at onshore oil production. Outside of the Permian region, US onshore oil production has been flatlining for 10 years now

Now the Permian region has seen some consolidation. How you want to measure this is tricky - you can do production, wells, or acreage. I am going to use acreage for the simple reason that Bloomberg has already done it for me! The key here is after a number of deals have made a clear leading pack, and long list of second tier producers.

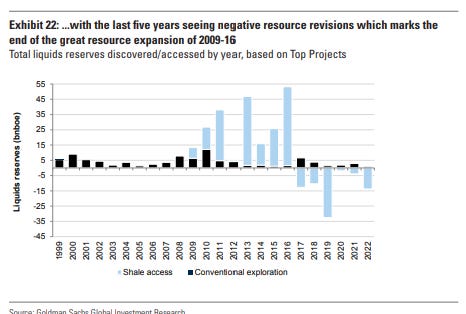

What this has been highlighting is that US producers have been spending on consolidation rather than growing production. As GS points out, total shale reserves has been falling last few years.

Goldman’s also highlights how shale has been the swing producer for oil industry. A consolidated US shale industry would raise returns across the whole industry.

High prices tend to bring about more production, and low prices tend to bring about less production. In the shale region, low capital costs and a surge for market share seemed to drive unlimited growth. My guess is the shale is close to consolidated, and supply close to being brought under control. If demand should surprise to the upside, either from a surging India or a recovering China then higher energy prices could reappear.