My focus on food inflation has been looking at the connections between pork prices and grain prices, as well as natural gas prices and fertiliser costs. The reality of both these areas is that recent price action has been more deflationary than inflationary. Chinese pork prices have fallen back to levels that were seen before the problems with African Swine Flu.

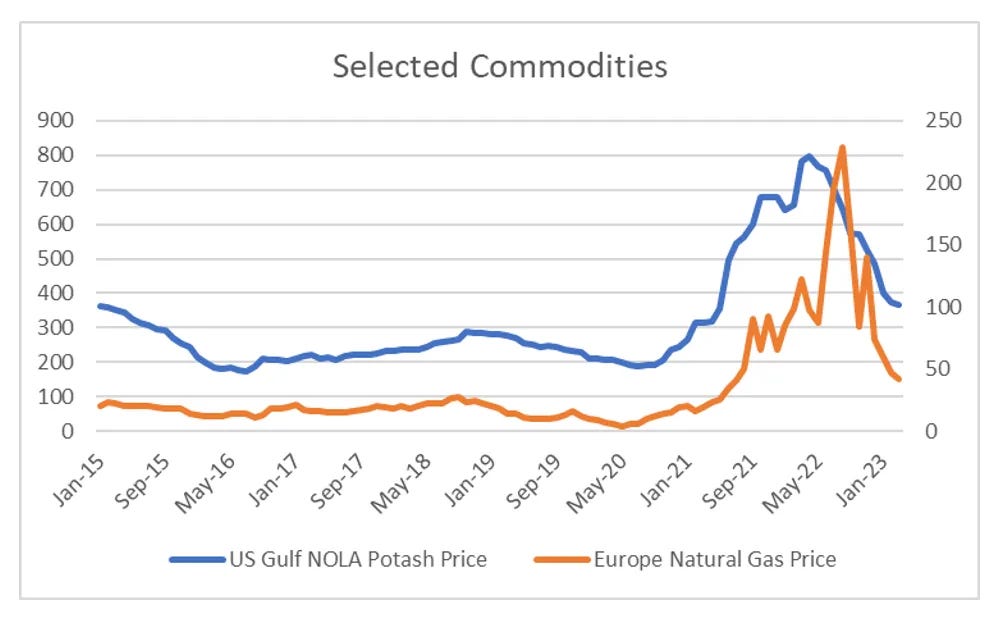

Fertiliser prices have also fallen back from the levels seen during the initial stages of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

With pork prices and fertiliser prices falling back, upward pressure on grain prices should have reduced. This should lead to less upward pressure on bread prices and food prices in general.

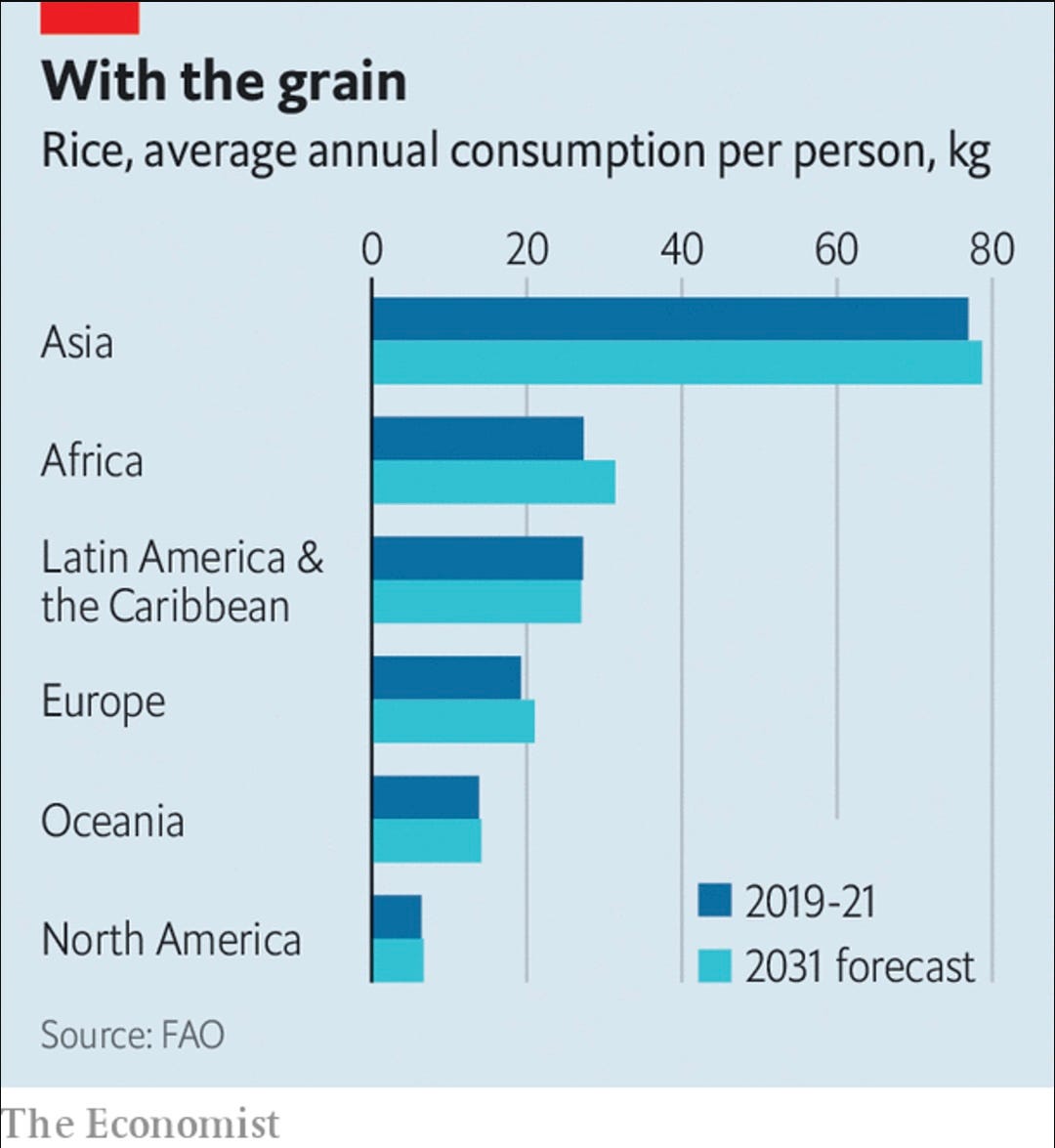

So the core idea of food inflation continuing looks challenged, and in particular by the fall in Chinese pork prices. But bread and pork are food items that Westerners can easily relate to. But while bread is the key food in the west, rice is the key food for Asia. And as the Economist infographic highlights, increasingly important in Africa and Latin America.

As you would expect, with the largest populations and largest per capita consumption, India and China dominate production of rice.

However, on an export basis, Thailand and India are the biggest producers, but with Thai exports declining recently, and Indian exports increasing.

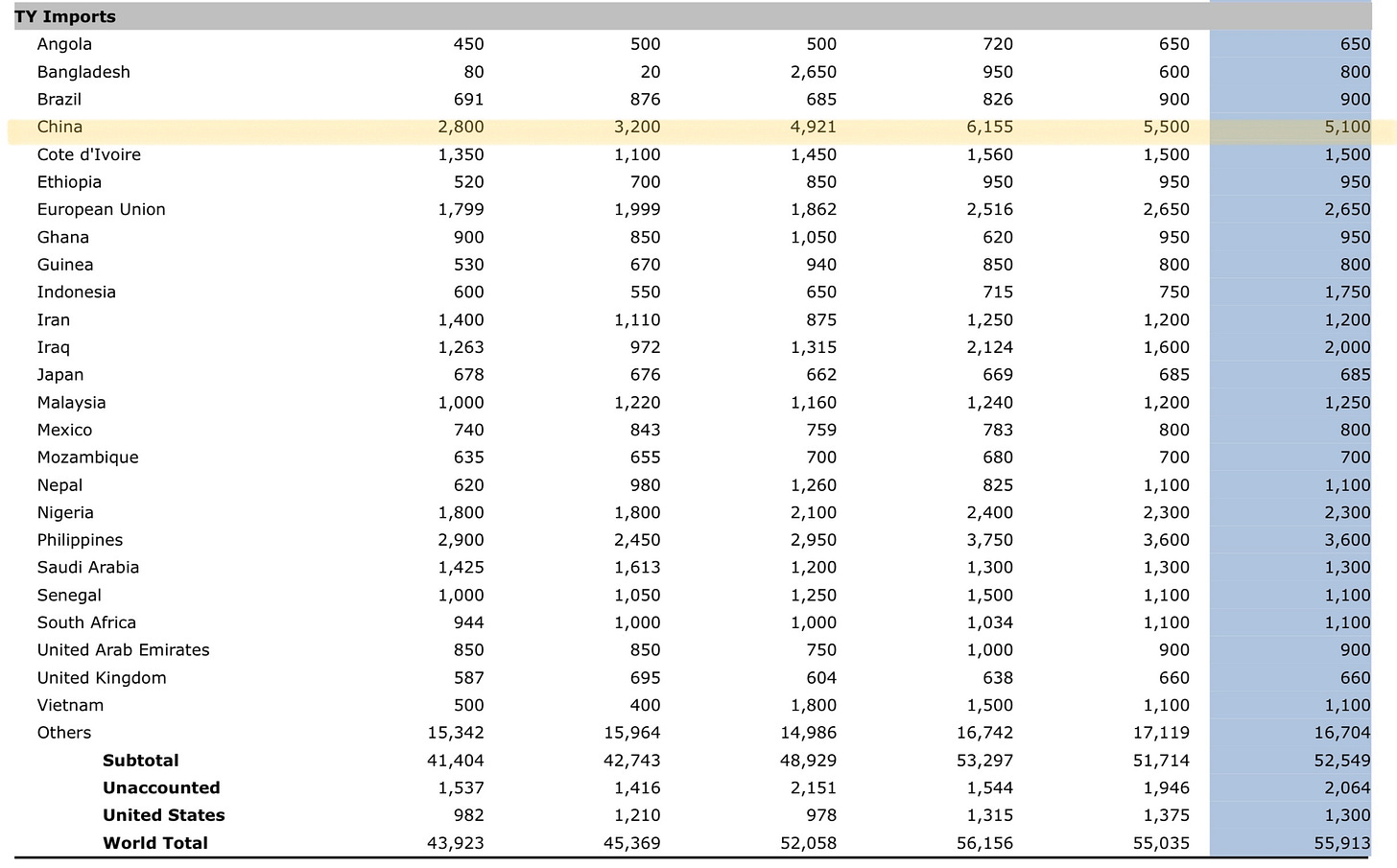

China has also quietly become the world’s largest importer of rice.

And unlike other grains over the last 12 months or so, rice prices have been gently rising.

What makes rice far more interesting for food inflation is that it is much more closely linked to wage inflation. Rice farming tends to be done at a small scale, and is far less mechanised than wheat, corn or soy, which are the only other products that approach the scale of rice farming. So rising manufacturing wages in China should have very strong effect on the cost of rice in China.

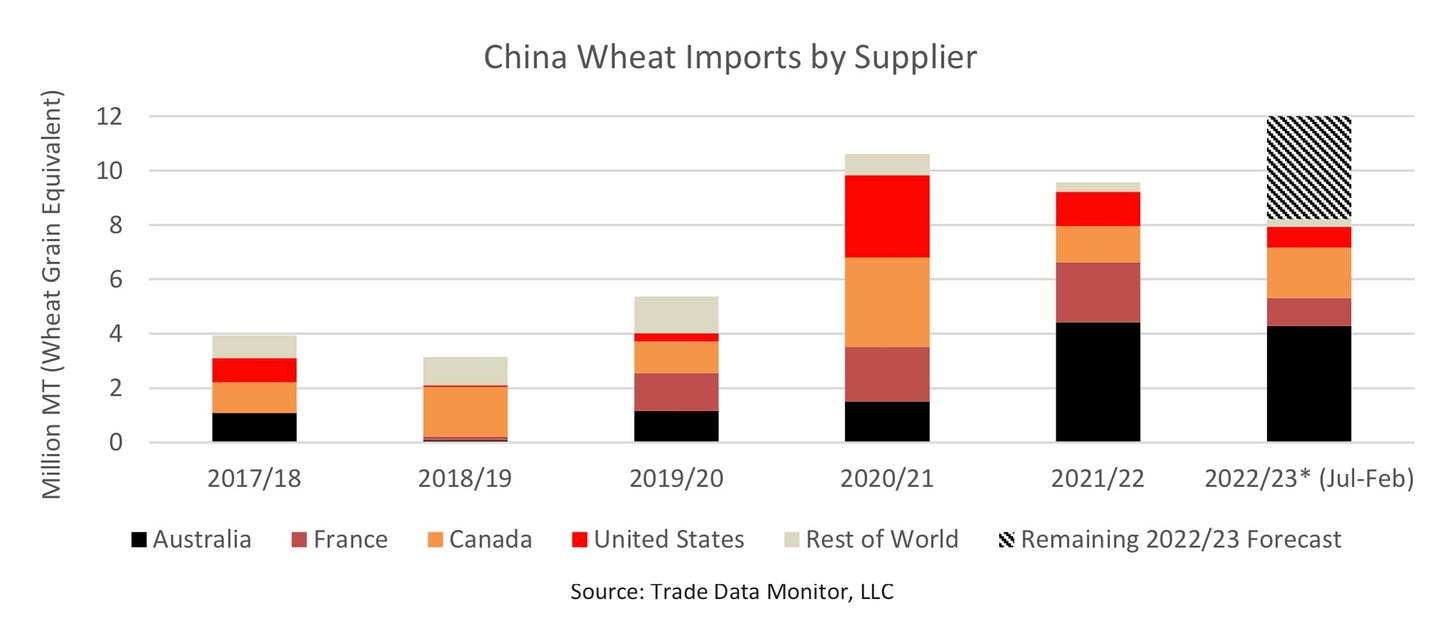

If China is having problems with rice production because it has high wages, the longer the Chinese Yuan stays stronger, the more likely we are to see wages rising in other rice producing nations, making it even more likely rice prices keep rising. Does this analysis mean that food inflation is likely to remain an Asian problem? Probably not. Despite weakening wheat prices over the last year, China has become the world largest importer of wheat.

The destruction of the Soviet Union ushered in a period of commodity oversupply. Unless China can be similarly destroyed economically, either through major recession or currency devaluation, food inflation looks like it is here to stay.