Despite concerted efforts by the current government, net migration to the UK reached a new all-time high of over 600,000 in 2022 according to the Office of National Statistics (ONS). Students are the single biggest group of immigrants, with over 361,000 arriving in 2022, up from 301,000 in 2021. In comparison immigration for humanitarian reasons rose to 172,000 in 2022 from 57,000 the year before, largely driven by one-off increases from Ukraine and Hong Kong. As late as 1992, the UK was a net exporter of people. At 600,000 net migration is 1% of the UK population, and makes the net immigration to the UK in line with other traditional immigrant nations such as Australia, US, and Canada.

The ONS notes that student immigration tends to be short term before reversing; however, Home Office data suggests a long-term trend at work here: the UK is allowing more students to come to study. Home Office data, which includes Q1 2023, shows that student visa issuance is at all-time high.

The Conservative Party’s target of bringing net immigration below 100,000 seems incompatible with an annual issuance of student visas of over 600,000. To meet its political commitments of lower immigration, the UK government could slash student visa issuance. However, this policy would be extremely problematic. According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) foreign students make up 25 percent of all students in higher education. For full-time post-graduate studies, they make up 65 percent of all students.

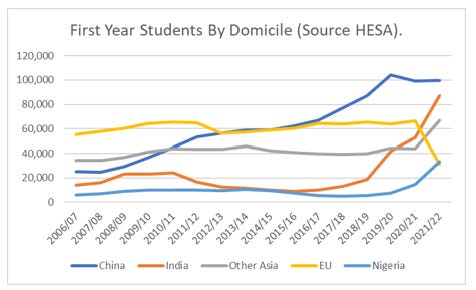

Foreign students pay much higher fees than UK residents accounting for over half the tuition revenue at major UK universities. The issue is that this revenue stream particularly relies on Chinese students, who combine a huge desire for higher education with the cash to pay for it. Tuition fees are by far the main source of income for UK higher education.

The success of the UK higher education industry conflicts with another government policy: to reduce economic reliance on China. Visas to Chinese students have fallen slightly in recent years, but this limits the ability of universities to increase tuition revenue. To diversify sources of students and grow tuition revenue, the UK now accepts more students from elsewhere.

In recent years visas to students from India, Other Asia (mainly Pakistan) and Nigeria have surged. The problem is that these students pay less than Chinese students. In addition, leaving the EU has also meant that EU students face higher tuition fees, leading to a decline in their numbers.

According to HESA, the most popular university for Chinese students in the UK is University College of London (UCL). At UCL, UK students pay £9,250 a year, while foreign students pay up to £31,270 a year. UCL is the highest earning university in the UK, pulling in £712 million in tuition fees.

The most popular university in the UK for Indian, Pakistani, and Nigerian students is the University of Hertfordshire, a former polytechnic. UK students pay £9,250 per year to attend University of Hertfordshire, whilst it is £14,750 for foreign students. The University of Hertfordshire is around the 30th highest earning university, with £235 million in tuition fees.

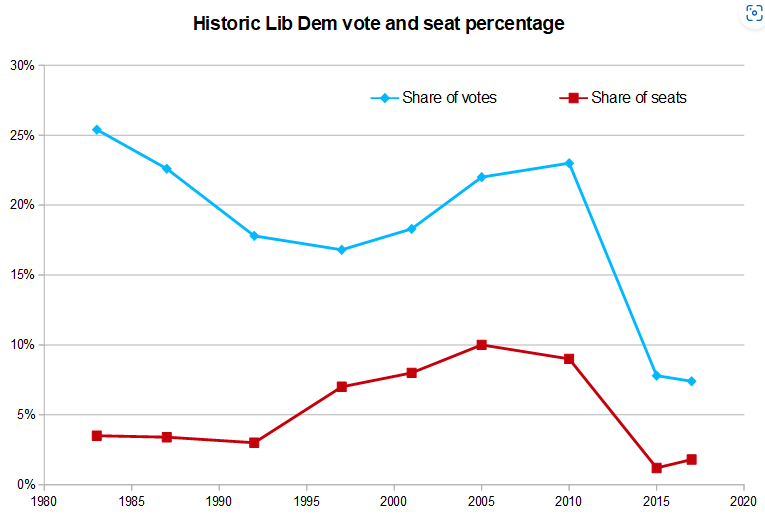

One way to reduce immigration would be to cap or reduce the number of Chinese students and raise domestic student tuition fees to compensate universities for the loss of revenue. Raising tuition fees is a deeply unpopular policy, though, and played a part in the implosion of the Liberal Democrats in the 2015 election.

The UK has loosened visa requirements for students from elsewhere, rather than raise tuition fees, but these students pay far less than Chinese students, so many more students are needed, which pushes up net immigration numbers. The UK government faces a choice between higher tuition fees, or high levels of immigration. Given the experience of the Liberal Democrats, the Conservative government apparently believes the political cost of high levels of immigration is less than the cost of raising domestic tuition fees. High levels of immigration to the UK looks set to continue.