In my school days, the constant criticism I used to get was not showing my working - to which I would reply, but its so obvious why would anyone need to see that? I have learnt, that showing your working is a good way to avoid mistakes - so I do try and show my working these days. Below is my effort to explain my view of why we are moving to an era of capital scarcity.

There are three interconnected way that the flow of capital seems to be slowing or even reversing. First, the uniquely modern phenomenon of buying government bonds for foreign reserves is going into reverse. Second, share buy backs are slowing, and thirdly, the private equity conveyor belt is slowing rapidly.

One of the first parts of my thinking is that many of the features of modern finance that we take for granted are rather novel. For example, sovereign wealth funds, and foreign exchange reserves made of other countries bonds are new features of modern economies. Back in the day, when trust was short (and perhaps in the near future), gold was the only asset that governments trusted. The idea of buying another governments bonds would have seemed ludicrous. What if they defaulted, or refused to pay you? There was a time of course when the idea that US would default on bonds would seem laughable - but in essence the Trump administration wants foreigners to stop buying treasuries and let the US dollar depreciate. Could the US not pay coupons or even principal on treasuries held by China? Sure. Japan? Maybe. As JP Morgan was quoted as saying, in gold is money, everything else is credit.

Buying treasuries as foreign reserves was apparently the brain wave of Kissinger, who convinced the OPEC nations to recycles their export earnings back into treasuries (the Petrodollar). However the long bear market in oil from 1979 to 2000 led Saudi and other OPEC nations to have largely run down foreign reserves by 2000. The boom years that have followed saw these petrodollar build again, before running down in recent years.

Japan was truly the nation that invented the vast foreign exchange holdings that we see in the world today. Uniquely in the world, Japan has almost no gold holdings. That is Japan went all in on buying treasuries to keep the US spending tariffs low, and to finance its military umbrella.

In the “pro-capital” era that ran from 1980 to 2016 or so, governments would happily devalue to get their economies going again. And in the Japanese case, buy treasuries to try and keep Yen weak. In practice, labour costs and inflation was kept low, and this cause a substantial increase in the amount of capital available. If the world economy is growing, but most of these gains are going to capital owners and now workers, the available capital must be growing. Can we track this in any meaningful way? Total foreign reserves to world GDP peaked in 2012 and has declined substantially since. It should be pointed out, this measure excludes gold. This is not a perfect measure, but it is indicative.

The second sign of a change from abundance is the change in share buyback dynamics. In the era of capital abundance, companies could return huge amounts of capital to shareholders. Again a very novel feature has been the falling share count of the S&P 500. Companies focuses heavily on generating and returning capital. Recently, that share count has been rising again. For me, its a sign that corporates no long generate excess capital.

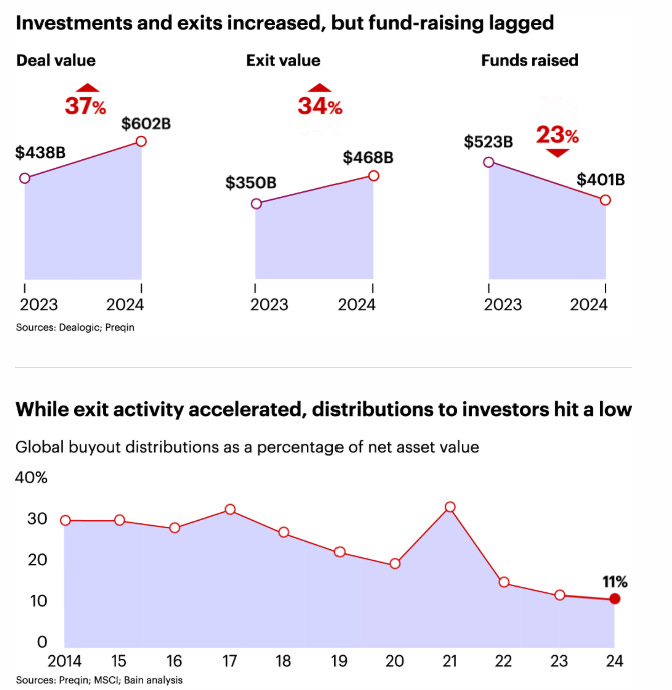

Finally, the private equity bubble seems to be slowly unwinding. 2024 was the first year we saw AUM of buyout firms not grow. In simple terms, they could not raise enough capital to offset distributions.

Exit values were substantially below funds raised. And last few years, distributions as a percentage of NAV has been low.

One of the more “red flag” trends in private equity has been sponsor to sponsor deals. That is where a private equity firm sells to another private equity firm. It raises the question of what is the strategic rationale, other than doing a transaction to generate fees. 2024 saw a 140% increase in such deals relative to 2023.

Above sponsor to sponsor deals, and falling distribution rates suggest the capital generation of private equity is becoming more difficult.

Bain analysis shows the industry is seeing cash flow becoming more negative in recent funds.

In a era of rising tariffs, and more government intervention in supply chains, as well as a militarisation of Europe and Asia, money has to come from somewhere, and increasing it looks like corporates are bearing the brunt. With higher interest rates and higher costs, private equity capital generation looks constrained.

Of all of these are interrelated - as government seek to keep real wages higher, cash flow to corporates drops. As government run down reserves to defend exchange rates, or stop intervening to keep exchange rats low, the amount of capital available falls. This means interest rates have to rise. Japanese 10 year yields continue to rise, making investment in risk private equity less attractive.

All of these are driven by the populist bent that politics has taken. The new Trump administration is forcing change, and the end of the natural accumulation of capital by corporates, and its recycling back in to the US. The end of capital abundance and an era of capital scarcity beckons.