One thing I learnt from my American friends over the years is that the profit incentive is the only thing that can be relied on in the US. And there is a lot to be said for such a system. It is transparent, it rewards effort, and when money is the centre of a political system it allows for concessions and agreements (you can always buy off your opponents). Broadly speaking, when I talk of pro-capital policies, I talk of policies that favour corporates over workers, and more generally corporates over governments. Privatisation was the transfer of public assets to the private sector. But it was not only the transfer of assets, it was the removal of government controlled competition from the private sector. The “problem” with this theory was that government controlled institutions could not fail by definition. As more businesses were privatised, the business cycle became more brutal, and governments needed to spend ever more to keep the cycle going. So despite strong growth and wealth creation, the US government has become ever more indebted.

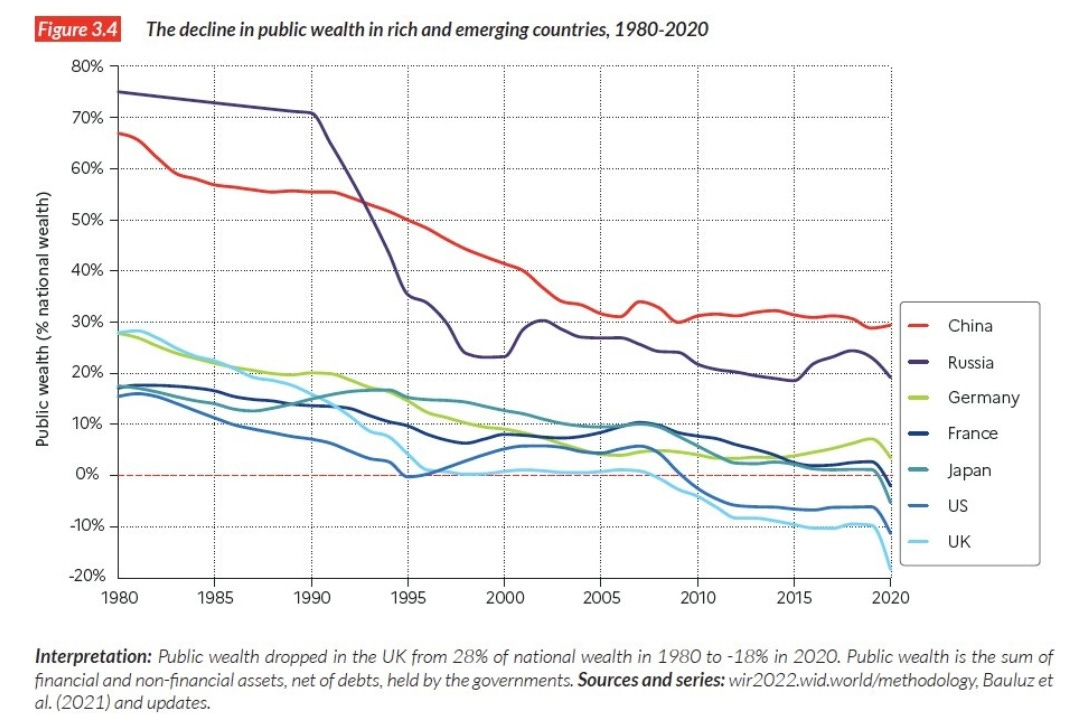

In the UK and the US, public wealth is now negative. That is the combination of privatisation and then government spending has led the net assets of government to be negative. This seems to be the obvious end game for pro-capital policies. The question then, what is the basis for government bonds being risk free assets? The obvious answer is that should governments need or want to, then they can easily nationalise or tax as need be to pay off debts. But here is the paradox of the US. Both major parties seem committed to increasing spending, and not raising taxes (well both parties love increasing spending, and the Republicans are committed to cutting taxes). And that is the mystery of US treasuries. They are a government obligation, but the political ideology of the US is for an ever smaller state - and ever increasing corporate sector. And absent some crisis that causes a sea change in domestic politics, it is hard to see how tax rates for corporates might ever rise (the movement in people from California to Texas suggests a secular trend to lower tax collection).

The market has picked up on the political winds in the US. During the recent debt ceiling negotiations, the 5 yr CDS on the US has risen to 54. Not high by emerging market standards, but very high by US standards. And very odd if you consider that with high house prices, and full employment, the US should be a very safe sovereign credit.

The problem for holders of US treasuries is that the market does not price in problems for US government debt default into corporate issuers. If we look at Apple, its 5 year CDS has barely moved even as the US looks more likely to default. The market is probably rightly saying that the US may well default on its debt, and leave corporates be. Can I imagine a scenario where the US decided to default on it debt, but Apple continues to pay its debt? Well I can.

This change in risk pricing is probably correct. Apple operates globally, and famously avoided paying tax in Europe for many years. It could probably avoid any tax grab on its resources if push came to shove, or pay lobbyists enough to avoid paying tax. The market seems to waking up to the fact that the US does not really face any strong disincentives to defaulting on its debt. The way markets have evolved over the last few years makes this even more likely. Talk of debt default has not seen the US dollar weaken (which is a way of defaulting on debt to foreigners).

Also big owners of treasuries are the Federal Reserve and Central Banks (China still has nearly a trillion in US debt). They are easy to default on than the US public. What makes this more likely is that US corporates saw neither bond weakness or equity weakness during the debt defaults talks. If they see no downside to US debt default, then why would they accept higher taxes? Treasuries are hard to understand as risk free assets with the current US political set up.