A few years ago, I looked at the rise of populism as the rise of “pro-labour” politics. I saw the return of industry policy, tariffs, unions and fiscal spend as all designed to raise the share of wealth going to workers and to reduce the share going to the owners of capital. To me it meant inflation would be entrenched, UNLESS, central banks acted to tighten monetary policy. So I put on a long gold, short treasury trade. It has done well.

Now if I was a typical fund manager or substack writer, I would just say, “hey, I am a genius - pay me tonnes of money please” and leave it at that. But I am not typical. I thought an environment where yields were rising, and gold was rising would NOT be a good environment for equities. Owning the S&P 500 has been absolutely fine for investors - although recently you have lagged gold.

I could make an argument that I was right about gold outperforming S&P 500 But I did not see the Korean market breaking out to new highs in this analysis.

Or the Nikkei for that matter.

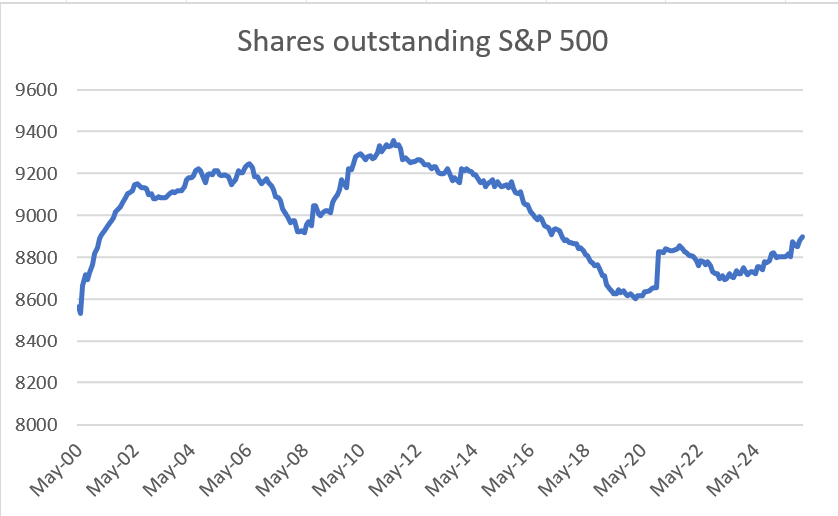

How can we make sense of all this? What is becoming increasingly apparent, to me anyway, is that the corporate world has been underinvested for the surging demand created by “pro-labour” policies. Insourcing or friend sourcing and various industrial policies have created huge demand back in the developed world. But many developed world corporates, there has been such a focus on building moats, raising prices, and returning capital to share holders, we have become chronically underinvested. If you look at shares outstanding in the US, they have only just started to rise. A rising share count implies selling equity to raise capital to me.

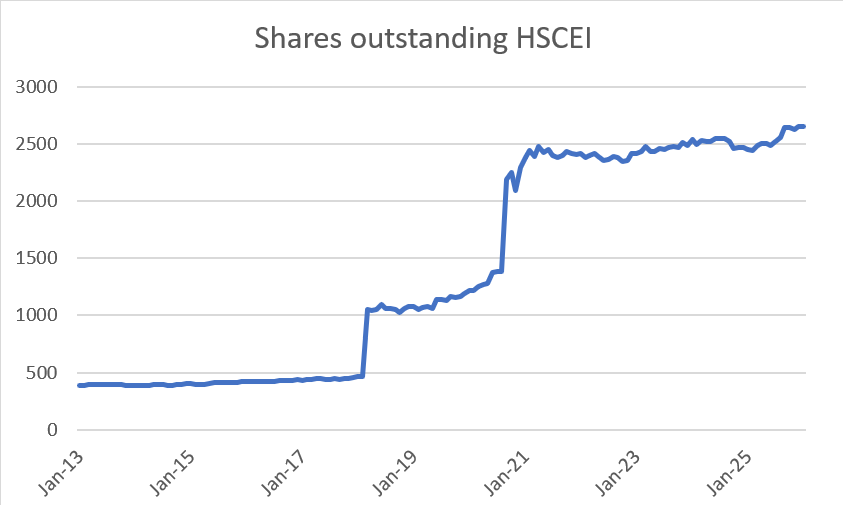

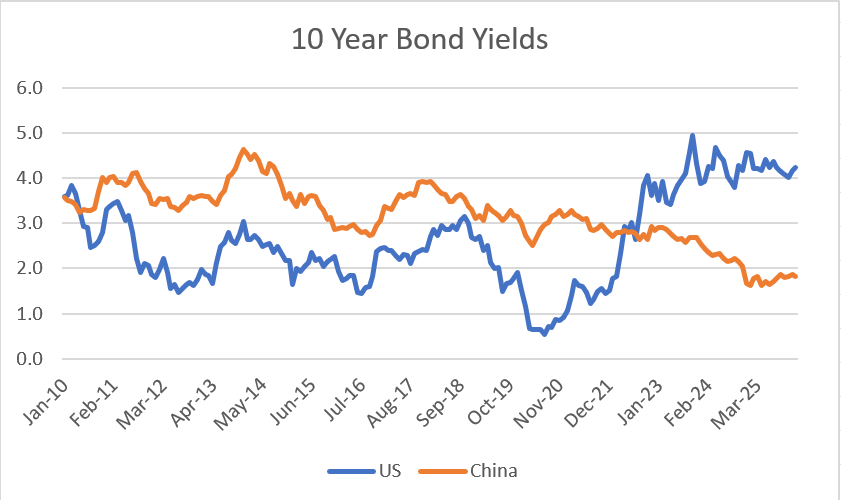

China, which does not have the same focus on share buy backs, seemingly faces less of the capacity constraints that faces US corporates.

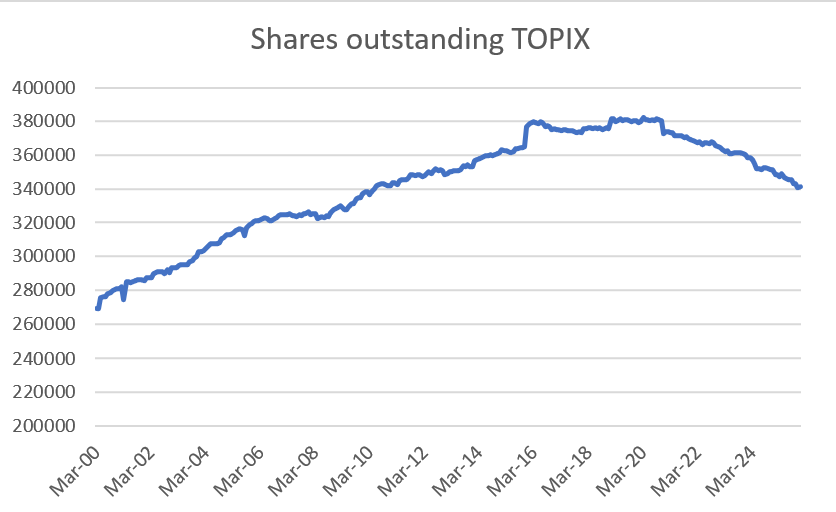

In a way, what I am saying is that when markets reward share buybacks over investing, at some point you will get a surge in inflation. Japan was like China until 2020 or so, and now looks like the US in 2012 to 2018 era.

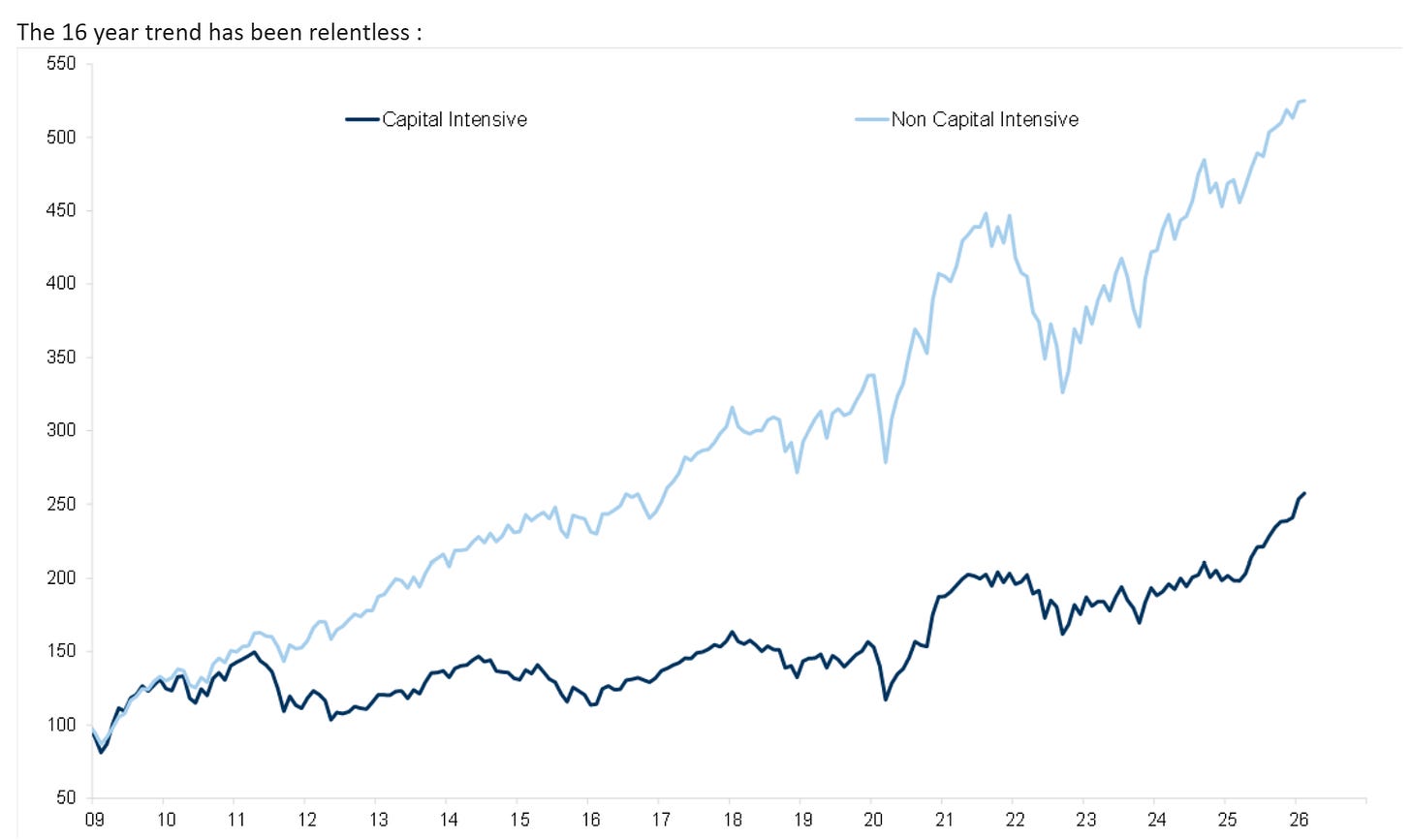

As Mark Wilson over at GS points out, the market has rewarded capital light businesses for years now. Or in other words, markets have rewarded companies for not investing.

But that is beginning to change.

The market is screaming out for companies to sell equity to fund growth. But so far, corporates remain constrained in their equity issuance, despite the market signals.

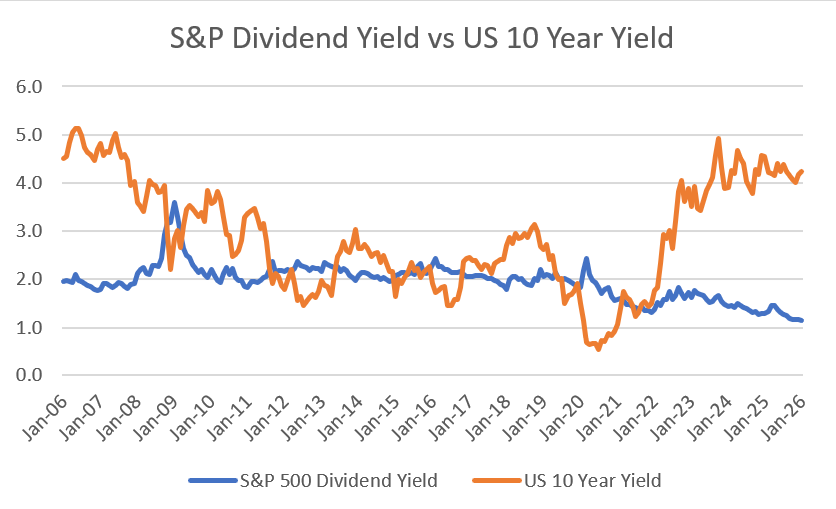

So I am now left with two possible reasons for the movement in GLD/TLT. One is political, that we are shifting pro-labour, and wages will rise dramatically. Or a second one, that years of share buy backs and “pro-capital” policies have left the western world (or everywhere but China), chronically underinvested. From this interpretation, looking at relative government bond yields, the market decided that the US was underinvesting in 2021 relative to China. But if you look at China, it has surging production in almost all good, and electricity, while the rest of the world faces backlogs. The market seems to imply China still over invests.

So GLD/TLT could well be moving because the world (outside of China) is chronically underinvested. That would chime with the surge in capital heavy stocks. The question will be when will we have invested enough? Or alternatively, when do politicians act to restrain demand? Looking back at the “pro-capital” era that ran from 1980 to 2016 or so, it was driven by a US that felt it had no real rivals. Both the Soviet Union and Japan, both seen as military and economic rivals, were beaten back in this era. A US that feels safe in its own position, could then revert to its free trading ideal I think. But for the US to feel safe today, it would need to feel it has defeated China, or at the very least engineered some sort of regime change in China. For me, the US and West missed their opportunity to change China in 2015. Then the economy as in freefall, with capital fleeing. If the US has instigated tighter fiscal and monetary policy at that point, then an Asian Financial Crisis style disaster would have befallen China - and regime change would have followed. Instead we chose more QE and negative interest rates. What GLD/TLT tells me now, is that the price of regime change will be much higher. But I guess that’s politics.

And to answer the original question, pro-labour policies have created capital scarcity - they are two sides of the same coin. Now we just need to wait for much higher interest rates.