I had my first impostor for this substack this weekend - that must mean I am bigtime! Apologies for any inconvenience, and now I know I am a potential target, I will be extra vigilant.

Long time readers will know I have a strong interest in fertility trends. It fits in with my interest in attacking consensus positions. And the Economist is very consensus on this topic. Basically, they make two points. The drop in fertility comes from ending teenage pregnancies and that attempts by governments to pay women to have more babies have failed. Following this logic, unless we adopt Handmaiden-style fertility policies, we will inevitably see falling populations. To simplify, they see the world becoming more Korean, than Israeli.

The Economist finds falling birth rates a structural issue, which no amount of government spending can change. I think this analysis is flawed. First of all, as you can see above, Israel has managed to achieve high birth rates. Politics in Israel is strongly pro-natal, with government committed to helping any woman achieve at least two pregnancies. That is rather than offering a fixed sum to try and promote pregnancies, the government makes an open ended commitment. That is Israel ends up spending less than other nations shows how effective this policy can be.

Looking at US data, birth rates for young women have collapsed, while older women have maintained fertility rates. A trend to being an older mother limits fertility rates is the argument, again making declining fertility a structural issue.

Getting rid of teenage pregnancies is a good thing. But what is unusual is how relatively recent this phenomenon is. Using UK data, which goes back to before World War II, we can see that the age at which women first became mothers dramatically dropped after World War II, before rising again. Given improvements in general health and medicine, a three year increase in when women first become mother between 1939 and 2020 does not seem to me to explain declining fertility. A good question to ask is why women became mothers earlier after World War II. At that time, like Israel today, the nation became very pro-natal, and the roll out of universal healthcare, and other pro-labour policies offered the support young families needed.

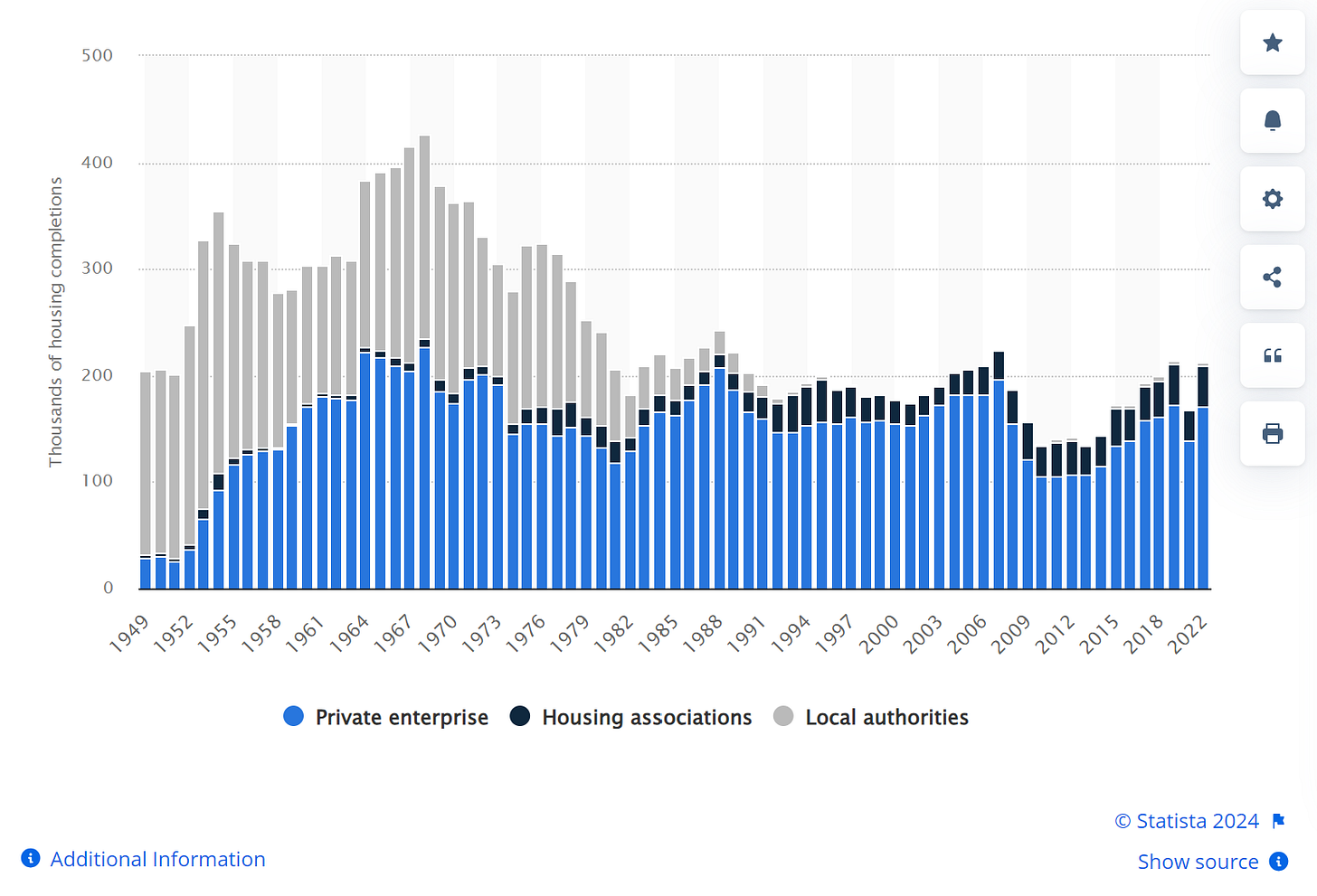

Another feature of a pro-labour policy is making it easier for families to grow. If we take the UK, and my own personal experience and that of my friends, having a family means contemplating the expense of a larger home. When government policy is to supply homes that makes having a family easier, then expect more kids. When policy is to reduce supply of homes, and drive up housing prices, falling birth rates seem a likely outcome. If Labour win the next UK election, they are targeting a substantial increase in home building.

Political trends, which are pro-labour, should also be pro-fertility in my view are turning. On top of this change, technological change is beginning to turn pro-fertility. First of all, women are realising that its not the age of the woman that determines whether IVF is successful or not, but the age of the egg. Donor eggs will almost always be from a women aged 30 or below.

In the UK, we have seen a sea change in IVF, with frozen eggs become the main way that IVF births are realised. That is technology is catching up with the needs of women that wish to have children later.

We can also see that generational change in attitudes to child birth are beginning to move pro-natal. Using Swedish data, we can see that mothers born in 1972, tended to have children earlier. Mother born in 1982, tend to have children later, which would naturally push down fertility rates. Mother born in 1992, are following the trend of mothers born in 1982. This means the fertility headwind is at least turning neutral, and potentially turning to a tailwind.

In some ways, the Economist is right - paying cash for kids will not work. But a policy that favours workers, giving better healthcare, affordable housing and more job security would likely lead to higher fertility rates. Governments just need to move away from pro-capital policies that lead to high property prices, threadbare public health systems, and employment policies that favour corporates. That is happening in my view, and best lead indicator for me is frozen embryos and eggs. It is a strong indication of the intention to have children, its just requires the financial security of pro-labour policies to turn intention to reality.

Just as the world (and the Economist) was caught out by the effectiveness of policies to reduce birth rates in the 1980s and 1990s, I suspect they will be caught out by policies to promote birth rates in 2020s and 2030s. Here comes the baby boom!