THE COMING DEBT CRISIS IN BRAZIL?

“One of the most amazing things about the investment industry is how it can get things repeatedly wrong over many years and then never pause to reflect on where it went wrong.

The current debt crisis in Europe has exposed two things in my view. Firstly, the key sign that a country was getting into trouble, came from a widening current account deficit. Ireland and Spain both had very low levels of government debt to GDP, but gaping current accounts. This was also true of the Baltic states before the financial crisis in 2008, when they were forced to seek IMF help. Secondly, governments which become dependent on tax revenues from a single booming industry can quickly see public debts escalate when the boom ends. This was the case in the US, UK, Ireland and Spain when the housing boom ended in these markets.

The performance of Brazilian assets over the last 10 years has been extraordinary. Investors in the Brazilian stock market have seen a return of over 1000% as commodities markets have boomed, and exports have surged.

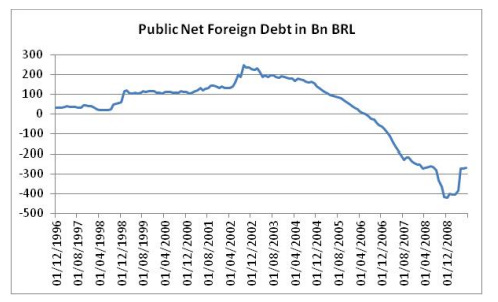

This surge in exports and a boom in foreign direct investment into Brazil has led to massive improvement in the government’s net debt position.

The improvement in Brazil’s debt profile has seen a collapse in the risk premium that the market has asked for Brazilian assets – as can be seen by the movement in Brazilian CDSs.

As mentioned in the introduction, good aggregate data can hide some warning signs. First of all, Brazil has had a negative and widening current account deficit for over 5 years.

As a percentage of GDP the current account is only 2%, which compares favourably with 4% in 2002, when Brazil last suffered a debt crisis. Although, should exports prices fall, the current account would widen very rapidly.

Recently, the private sector has been borrowing aggressively, more than counteracting the improvement in government finances.

Brazil’s growth has also been supported by the government’s expansion of its social security programs and the chart below shows monthly government revenue and expenses in billions of Brazilian Reals (“BRL”) over the years. This data is taken from Bloomberg.

The Brazilian government has seen its tax revenues increase largely from strong growth in mining, oil and banking. Brazil has a very complicated tax system, making it difficult to calculate how much tax has been paid by a corporate entity. Fortunately two large corporates provide us with some numbers on their total taxes paid.

The discovery of oil has been a major driver of recent revenue growth. Reading through the 2010 annual report of Petrobras, we find that the company pays a number of taxes to the Brazilian state. It pays a royalty of between 5 to 10% of gross revenues on production. There is also a special participation charge of 0 to 40% on net operating revenues depending on the profitability of oil fields in question. The company, like other Brazilian companies, pays a Domestic State Tax (ICMS), Civil Servants Savings Program (PASEP), a Contribution for the Financing of Social Security (COFINS) and a Contribution for Intervention in the Economic Sector (CIDE). After all this Petrobras also pays out a dividend, which the state takes directly as a majority owner. Taking all this in to account, on my calculations Petrobras contributed nearly 91bn BRL to state coffers in 2011 or about 35% of its total revenue, or roughly 10% of total government tax take.

Itau Unibanco is the largest private bank in Brazil. In their 2010 annual report they state that they paid taxes of 11.8bn BRL and withheld and passed on another 8.6bn BRL in taxes, giving a total of 20.6bn BRL in 2010. The Brazilian banking sector is highly consolidated, with three of the 5 largest banks being state owned. On my calculations, the financial sector provides another 10 to 15% of total government tax take.

Given that both Petrobras and the banking sector have grown substantially in recent years and contribute significant parts of revenue to the government, the fact that Brazil still has a debt to GDP ratio of above 35% is particularly worrying. As seen below, debt levels in Brazil rise quickly in periods of weak commodity prices – during the 5 years after the Asian Financial Crisis and the 1 year fall in commodity prices in 2008.

Another tell tale sign of economic problems is when industry begins to lose competiveness. The Financial Times reported last year that US exports of ethanol to Brazil have soared over the last few years. This in part due to rising sugar prices and weak production, but given the inherent advantages of sugar production in Brazil this is very worrisome. Furthermore, market commentators report that a local Brazilian railcar maker is sourcing steel from overseas. Given the abundance of iron ore in Brazil and the high cost of transport for steel, this indicates that domestic costs in Brazil have risen significantly above productivity improvements.

Brazil has become very reliant on foreign direct investment into its oil and gas industry over the last few years. According to the Banco Central do Brasil, 53% of FDI from 2006 to 2009 was into the oil and gas industry. It predicts that oil and gas will take an even larger share going forward. Most of this investment is going into the technically challenging off shore oil fields that have been discovered in recent years.

While the oil price has been very strong for the last few years, it is becoming apparent that shale gas drilling techniques are beginning to offer a very attractive alternative energy source. In my opinion, Brazil runs the risk that natural gas supplies begin to exert downward pressure on oil prices. Current US natural gas prices are the equivalent of USD20 oil price on an energy equivalent basis, and reserves estimates for shale gas in Europe and China indicate that the US is not alone in being able to exploit shale gas. Brazil is very reliant on commodity prices staying high.

Brazil, unlike peripheral states in Europe, has a free floating currency and we would expect that any adjustment in Brazil would occur through the exchange rate rather than the bond market, as was the case in the US and UK after their housing busts. However, there is a problem with this (relatively) benign view on Brazilian fixed income securities.

Currencies that are devaluing to achieve financial stability generally fall by the amount of excess inflation that has built up in the economy. To estimate this I look at rebased CPI indices. On this Brazil has seen domestic prices rise by 110% since 2000, compared to a 30% increase in the US. This suggests risks of a significant fall in the Brazilian Real. As a guide, the BRL sold off by more than 60% in 2008 before quickly recovering with the markets.

In the debt crisis of 2002, Brazil had a high proportion of its public debt denominated in USD. The Central Bank was forced to raise rates to stabilise the currency, but this also choked off domestic demand causing GDP to contract and markets to enter a vicious circle. Since then Brazil has improved its debt profile by retiring USD debt and replacing it with debt linked to local interest rates and inflation. Brazil has over 31% of its government debt inflation linked, with another 21% floating.

My key concern is that historically Brazil has seen a very quick pass through of higher import costs as its currency has fallen. In my mind it is relatively easy to imagine that a falling BRL forces higher inflation, which raises interest costs for the government just as tax revenues are falling. The Central Bank may then be forced to raise rates which further adds to the cost of government debt.

Currently, Brazilian dollar debt yields less than a 1% premium to USD dollar debt. This is historically very low. The market has a view that Brazilian government finances are stable and safe. I see them as being reliant on a commodity story that is looking increasingly weak.