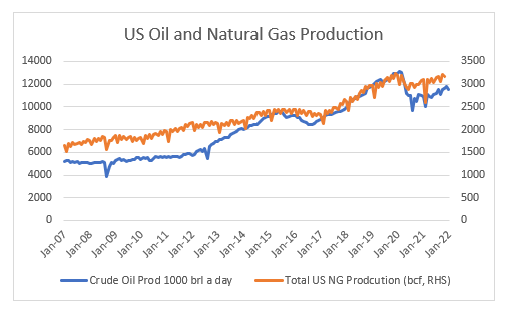

There is no question that shale drilling has transformed the US oil and gas industry. Oil and gas production have doubled since the adoption of shale drilling techniques.

However the big problem for the shale industry, and particularly for oil production, was that shale had a very high “decline” rate. In essence, a new shale well would produce half of all of its output in the first year. What this meant, that the US oil industry had to find and drill an ever larger number of wells to grow production. Using EIA production numbers, we can split out new production, and the decline. In February 2020, on the eve of Covid, the US has produced 7.5m barrels a day of new oil in just the last 12 months, which was offset by 6.5m barrels a day of decline.

The very odd thing about shale drilling, was that most drillers failed to generate much cash, and were reliant on the credit and equity investors to supply capital. To justify high equity valuations, it was important for many of the drillers to show growth. Lease and pipeline obligations also encouraged drillers to pursue growth at all costs. This led many drilling companies to drill more wells then they needed, so they left them uncompleted. This led to the rise of “Drilled, Uncompleted” or DUC wells.

My working assumption was that many of these DUC wells would prove to be of very low quality, or be so close to other wells that when they were completed would lead to a substantial decline in the efficiency of drilling in the US. When we look at the Permian region, which is the main drilling region in the US, we can see the DUC have collapsed as many wells stored in inventory have been brought on line. Contrary to my belief, these wells have been productive, and oil production in the Permian region has hit new all time highs.

If shale drilling is sustainable, then it is likely that the US will continue to enjoy a large energy cost advantage over the rest of the world. US natural gas costs are substantially lower than Europe or Asia. As can be seen below, European and Asian natural gas prices have risen substantially, while US prices are still subdued.

If shale technology is transformative, which is looking increasingly likely, then it explains the breakdown in the relationship between the US dollar and commodity prices. Usually a weak US dollar is associated with strong commodity prices, and vice versa. But in 2021 and 2022 we have seen a strong dollar and strong commodity prices. A shale industry that works would explain this change.

If shale technology is sustainable, one question investors need to ask themselves is how long until US oil and gas companies begin to ramp up drilling again? Does shale also put a cap on energy prices and inflation? Understanding shale may be the key to understanding macro going forward.