For those of you not familiar with the term widowmaker - its a term used in financial markets to being short Yen, or short JGBs. The names of fund managers that have tried and failed to short Yen or JGBs over the years is a who’s who of the financial markets. In 2007 I knew we were getting near the top when Hungarian mortgage banks began offering Yen mortgages, which had also proven toxic in Australia in 80s and 90s. For that reason, I always used to keep an eye on the Yen and 30 year JGBs. If either the Yen or the 30 year JGB began to rally, crisis was brewing. So it has been conspicuous that despite equity weakness in the US, 30 year JGBs and the Yen are very weak, not strong.

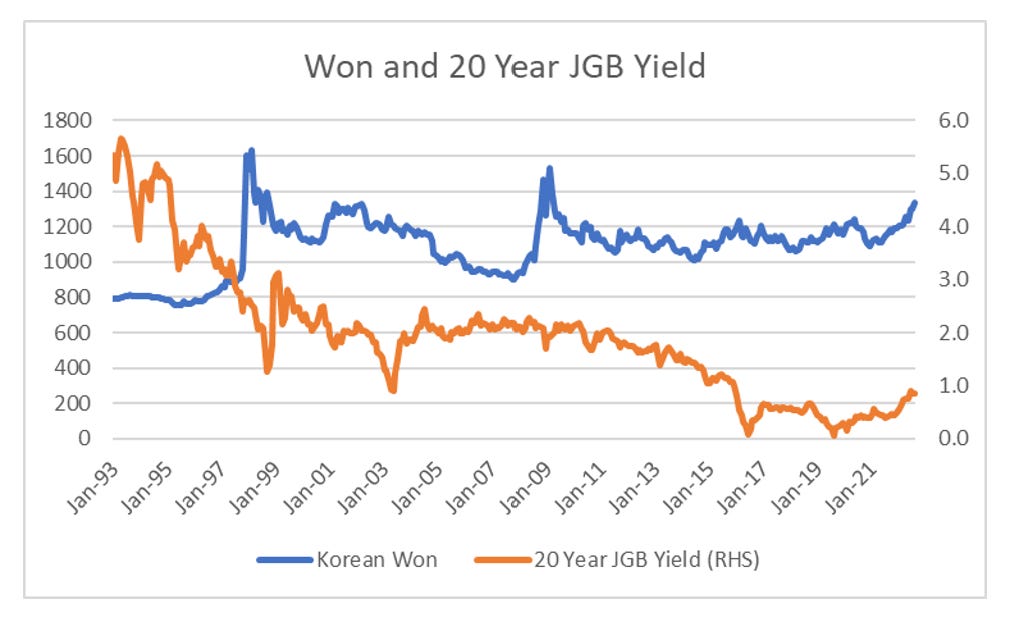

Despite most people being very bearish JGBs, I have made a lot of money being long JGBs unhedged from time to time. The bullish case for JGBs is (was?) that ever since the bubble economy burst in early 1990s, Japan had failed to create inflation. Why? Well whenever the Yen devalued, it would then cause it trade partners to devalue back against it. The purest way to look at this is the Yen versus the Won. Despite the BOJ best efforts since 1990, the Yen is still stayed at the level of 10 Won to 1 Yen since the Asian Financial Crisis. And if you believed in mean reversion, you would like want to be long Yen short Won here.

So in a free market, with free movement of labour and capital, the Yen depreciation efforts of the BOJ were totally self defeating, and when that became apparent via currency markets short positions in JGBs would be liquidated and cause JGBs to appreciate rapidly. This analysis would then lead me to look at the Korean Won, and generally want to buy JGBs when Korean won was weakening. In macro world, the Korean won has traditionally been seen as a good lead indicator on global activity. In 2022 that is not the case, Yen weakness seems to be driving the won weaker, but not causing deflationary pressure.

So what has changed to make the relationship between currencies and bonds change? So when a currency weakens you tend to see an improvement in exports and trade data. But I would argue that one area that would typically help the Yen and stop it from weakening is no longer a free market. Tourism has become a huge driver of growth, particularly from China, but restrictions have meant that the weak yen has had no effect on tourism numbers.

The increase in tourism has had a meaningful impact on Japanese tourism current account moving from a large deficit in 2000 (Japanese spending more overseas) to surplus before Covid (foreign visitors spending more in Japan).

Perhaps the other big change was that China is now a much bigger trade partner than Korea or the rest of Asia. The weakness of the Yen versus Chinese Yuan has been extreme this year. If there was free travel, you would imagine Chinese tourism numbers would be surging.

A surging currency in Yen terms would normally be seen as deflationary for China, and when we look at Chinese 10 year government bond yields, unlike almost every other bond market globally, bond yields have fallen in 2022.

In a free market, Chinese tourists would be flooding into Japan, Korean and other countries, and Chinese investors would be selling Chinese bonds to buy higher yielding bonds in Korea and other markets. But government restrictions on travel and the movement of capital is not allowing this to happen. So will China move back to free markets and then devalue? Will China reexport deflation back to Japan as Korea did in 1998 and 2008? China has a record trade surplus, making devaluation unlikely.

What is the conclusion of all this analysis? Traditional free market analysis would suggest buy yen and JGBs as Japan will see capital and tourism flows from China, forcing the currency up and being deflationary. Political analysis says the Yen will keep falling until the BOJ changes course, as China is under no threat of devaluation at the moment. This makes Yen tricky - it is a political call, not a macro call. But JGBs look like a short - the widowmaker trade might now be a moneymaker.