IS CHINA WINNING OR LOSING THE CURRENCY WAR? PART I

What does China's falling foreign reserves really mean?

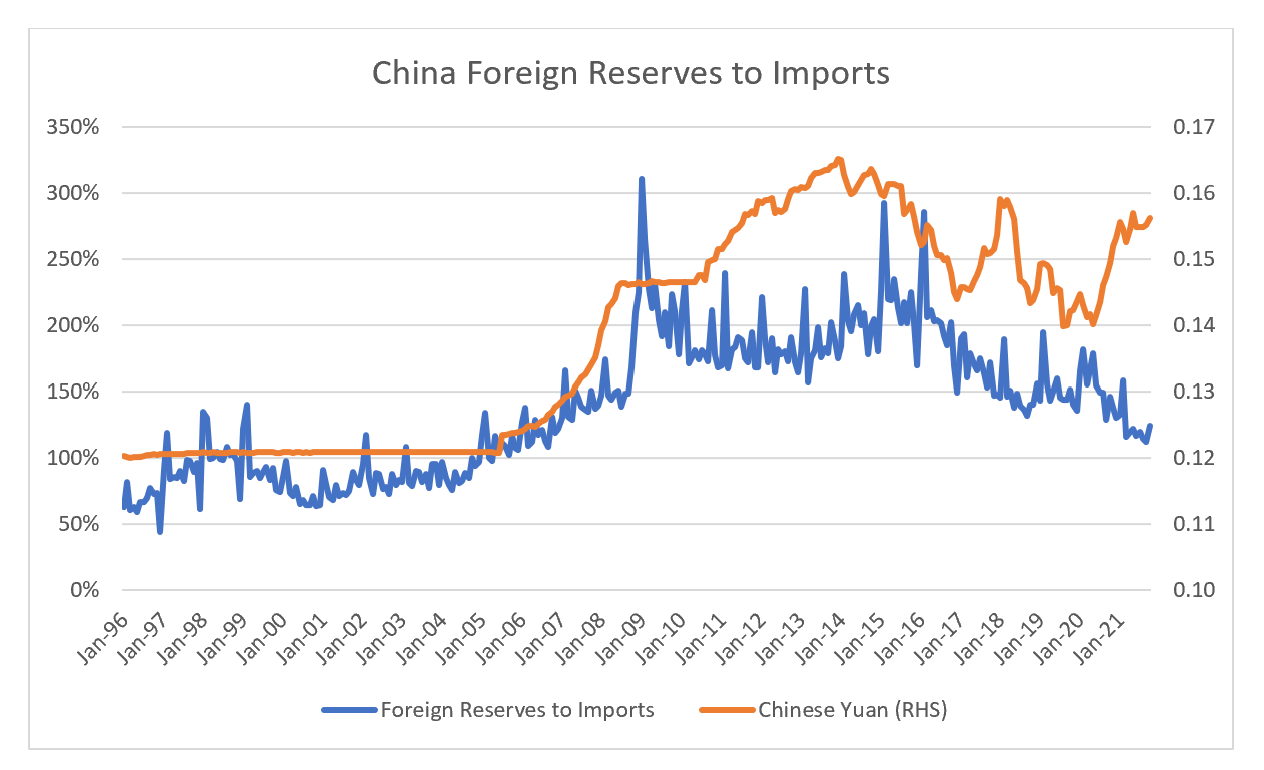

Amongst Asian exporting nations, China is the only nation not to see its foreign reserves build back to record levels in recent years. Does this mean the Chinese economy is under economic stress?

Under traditional emerging market analysis, falling reserves would be seen a sign of severe economic problems. For Korea falling foreign reserves in 1997 and 2008, were associated with severe currency and economic weakness.

One warning sign that the build up of Korean foreign reserves from 2002 to 2007 was not enough was the falling ratio of foreign reserves to imports. That is the dollar amount spent on imports was rising faster than reserves.

Looking at Chinese foreign reserves to imports, the ratio has been in decline since 2016, but unlike Korea has yet to show any significant currency weakness. The implication is that the Chinese Yuan is severely overvalued, and we should prepare for currency weakness.

Another sign that rising Korean foreign reserves were not going to act as a support for the currency comes from a declining share of foreign reserves been held as US treasuries. Japan, which has a safe haven status, holds almost all of its foreign reserves in US treasuries. Korea is typically closer to 30%. In times of crises, foreign reserves not held in US treasuries can be illiquid and difficult to sell. China is much closer to Korean levels than Japan. Hence the Chinese Yuan should have a currency profile similar to Korea than Japan, that is more likely to devalue.

If we assume China is determined to maintain a strong currency, then it is also trading and acting very differently to previous examples. At the tail end of the Asian Financial Crisis, the Hong Kong dollar peg came under speculative attack. Foreign reserves fell by a relatively small amount, largely due to extremely punitive interest rate applied by Hong Kong authorities to discourage betting on the peg breaking.

However the crisis did spark a property bear market in Hong Kong property, which did not see property prices recover until 2010. While Chinese property prices have slowed, there has been nothing like the decline seen in HK property from 1998.

Previously, foreign exchange reserves falling would imply either currency weakness or property weakness, however in China’s case neither has happened. One view is that China has exhausted its defences, and if the US begins to raise interest rates then severe currency and property weakness is likely. But there is an alternative view. Perhaps China does not need US Dollar reserves anymore? If that is the case, then we need to think about the world in a very different way. I will write about this in Part 2.