Big changes in the market are always foreshadowed in my experience. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was foreshadowed by the annexation of Crimea. China’s crackdown on tech companies was foreshadowed by the cancellation of the Ant IPO. The oil crises of the 1970s was foreshadowed by the formation of OPEC in 1960 and the US becoming a net importer of oil in late 1960s. So why were markets surprised by these events? Well financiers are not very imaginative - and they tend to think tomorrow will always look like yesterday. The most recent example of this is bond yields. The 40 year bull market in treasuries looks over.

But as I have noted before, investors have gone very long TLT as it has fallen over the last few years. That is most investors think nothing has changed.

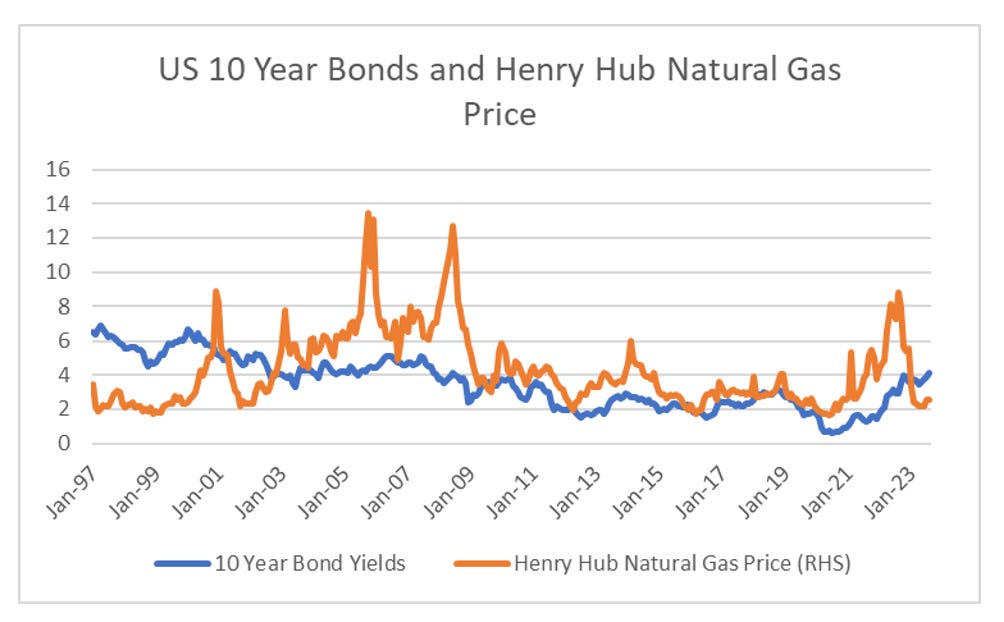

But the point of this post is not to laugh at bond investors, it is to look at what has changed to make the market think inflation will stay strong. Commodities and bonds have an uncertain relationship. Certainly bond yields peaked when oil prices peaked in 1970s, but since then the relationship to oil prices and bond yields have been erratic.

You could argue that natural gas is more important to the US economy than oil these days, just as oil took over from coal. With spot natural gas prices down at pre-Russian invasion levels, why not bet on deflation? With commodity prices weakening, and a heavily inverted yield curve, a deflationary bet seems to make sense.

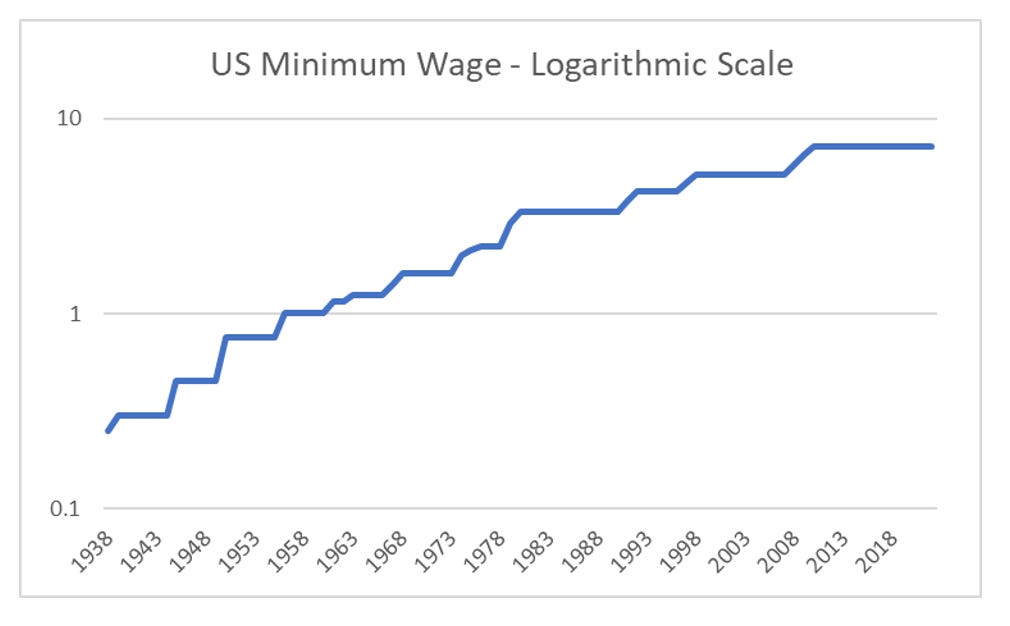

The thing is while back testing investment strategies is always useful, markets live in the future. And for me the political winds are changing. What makes more sense to me is that in the 1970s both commodity markets and bond markets were reacting to a policy that raised minimum wages aggressively. Conversely, bonds and commodities eventually reacted to a policy from 1980 onwards that did NOT raise wages aggressively.

So what political change has occurred recently, that could be as seismic as the minimum wage was post World War II. One such change in carbon pricing. Carbon pricing is a very political thing. Long term supply and demand is determined by political calculations. But short fluctuations are heavily influenced by economic concerns, but over the last year, falling energy prices have had no influence on carbon prices. That is the carbon market is pointing to a world where pricing carbon emissions says high.

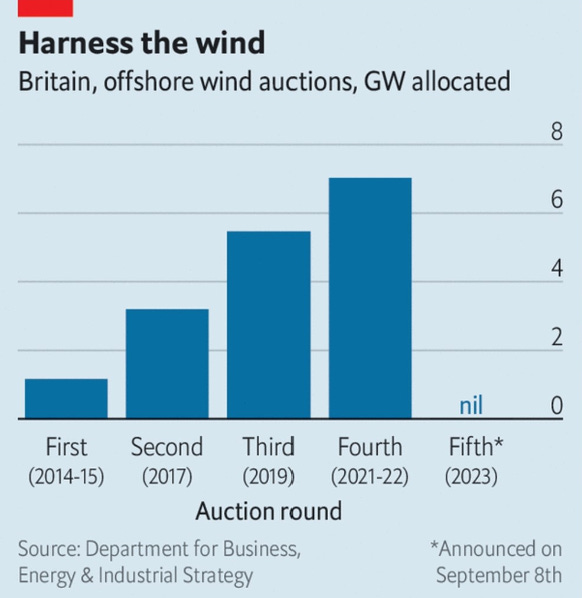

For me this represents the political commitment to pursuing green policy - in this case pricing carbon emissions back into prices. The commitment to keeping a carbon price high is becoming more important, as cost inflation is starting to wreak havoc in non-carbon energy sources. The most recent offshore wind auctions saw no bids in the UK. And this is despite high carbon prices.

The first round saw a price of £82.5 MW/h as a strike price, the second £74.75, the third round around £40 and the fourth and largest £37.35. The reason the fifth auction failed was a price of £44 MW/h was set as a cap, while building costs have surged. The declining economics of offshore wind is clearly visible in the share price of Orsted - a leading offshore wind farm operator. Renewable energy prices need to rise.

Voters want a green revolution (older voters are not so fussed but numbers and time is against them). A rising cost of carbon, which both incentivise green energy, and pushes up the cost of producing green energy looks inflationary to me. While carbon prices remain high they reflect a political world that is profoundly inflationary. Bonds remain a short.