CLEARING HOUSE MISPRICING

Clearing houses take a backward-looking view on risk. 2017 was the year of lowest average volatility ever but, as this rolls off the back of the look back period, will margins increase?

Central clearing houses did very well during the financial crisis. As LCH (London Clearing House – the largest interest rate derivative clearing house) states on its website, “LCH has a proven track record of handling defaults, managing the Lehman default ($9 trillion portfolio of 66,390 trades) and using only 35% of Lehman’s Initial Margin across all assets held at LCH.” Impressed with this performance, regulators have forced more and more of the financial markets to be cleared by central clearing parties (CCP). This has led to clearing houses and exchanges outperforming banks substantially since the financial crisis.

Clearing houses do not take a forward-looking view on risk. In fact, for the success of their commercial operations, their incentive structure is to make trading as easy as possible. Initial margins are the main limiting factor in trading for exchanges. How much do you need to put upfront to trade an asset? The higher the cost, the lower trading volumes will likely be. While clearing house individual initial margin models are proprietary, ISDA has been releasing an initial margin model for non-cleared futures since January 2017. This model has been licensed to all the main clearinghouses for their use so would likely be very similar to their own initial margin models. However the ISDA-SIMM model is reactive rather than proactive. An example of this can be seen in early 2018, when a spike in VIX caused the overnight bankruptcy of the short volatility ETN – XIV.

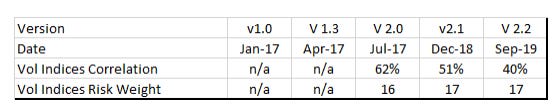

ISDA-SIMM models show how risky each asset is, how correlated it is to other assets, and give strict limits on the amount of concentration that should be allowed to a single counterparty. The idea is to limit the risk of a one day move wiping out either the exchange or other counterparties. The first risk weighting for volatility indices began in ISDA-SIMM model 2.0. Volatility indices at that time are given a risk weighting of 16 (this would be lower than a blue chip equity) and a correlation of 62% (meaning that two different volatility indices are highly correlated, so netting positions can reduce need for initial margin). The table below shows how the backward looking ISDA-SIMM model adjusted by lowering the correlation offset after the event.

Later on in 2018, as detailed by BIS, a single trader in European power markets nearly bankrupted a central clearing party in Sweden. (https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1812h.pdf) . In essence a trader had a very large long position in Nordic power hedged with a short German power position which had very high historic correlation. The relative move in the price of these two power markets is shown below.

Unlike with volatility, the ISDA-SIMM gave correlation and risk weightings for European power from version 1. Somewhat inexplicably, European power started with low risk weights, and low correlation discounts, but in July 2017, the correlation discount was raised to 100%. After the near bankruptcy of the CCP, and spread blowout, this was then reduced back to 73%.

While this may seem esoteric, the growing use of algorithmic trading, and passive investing means we can generalise some lessons. Initial margins will be very low during periods of low volatility, but will rise as volatility rises. In addition, if the price of the assets being traded is falling then the ratio of margin to position value rises further. This then forces deleveraging throughout the system. For example, even though the S&P was falling through 2008, the cost of holding the S&P future rose.

If we compare the cost of S&P Future margin to the price of the S&P 500 and VIX, then the relationship becomes clear. As volatility rises we would expect the margin as a percentage of the future to also rise sharply.

As we have seen from the ISDA-SIMM model, margins are set with a backward focus, typically between a three to five-year time frame. 2017 was the year of least average volatility ever, with average VIX of 11, which compares to a an average VIX in 2016 of 16. 2018 Average VIX was 16.6, and 2019 so far has an average VIX of 16. As we enter 2020, even if we only assume an average VIX for the year of 15, the back ward looking models will begin to raise margins, as the very low volatility 2017 rolls off the back of the look back period. Risks are all to the downside.

Hi, I remember reading the posts on your website about clearing houses and margin req’s changing due to volatility: https://www.russellclarkim.com/marketviews/russell-clark/2019/11/clearing-houses-and-initial-margin

It has always stuck in the back of my mind. With the firm and increasing bond vol (MOVE), and the more recent massive moves in european rates as wel as US equities, could a scenario like this be (or become) in play? Also given the sheer size of the otc derivatives on the balance sheets of various banks. It seems more relevant than ever.

How, other than the vol indices mentioned could/should we track or gauge this?

Thanks for doing this, it’s incredible valuable.