(The end of the article will update some thoughts on how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine affects China’s food supply)

China has long been the world’s largest food producer. But as it has principally be driven by the need to be self sufficient, it has not been either a major importer or exporter. However China holds by far the largest stock of grain. Well over half of total global stocks and six times as much as the USA.

It has often been wondered how much of China’s grain stock is real. Various audits over the years have discovered the grain to be inedible, or just not there. But give than China was largely self sufficient in grain, it was relatively unimportant to the rest of the world. This changed with the outbreak of African Swine Flu (ASF). ASF decimated the Chinese pig herd, and led to a substantial spike in Chinese imports of pork. As the Chinese pig herd has been rebuilt, imports of pork have fallen back to normal levels.

The rebuilding of pig herd has also made China require a big increase in imports of coarse grain (corn, sorghum and barley) used as feed for livestock. China has become the largest importer of grain in recent years.

Personally, I find it hard to square the idea of China having stocks of grain larger than anywhere else, and record imports of grain. The closest parallel I can come up with in the US in 1960 becoming a large oil importer while also being a large producer. When we look at world grain stocks, the US have fallen by near half over the last five years, while China still reports close to record stocks of grain. This would imply that production growth in China has been robust, but when we take a closer look at the Chinese agricultural industry, we find that for major grains, only corn has been able to grow production in recent years. This is very different to the 1980s and 1990s when production grew for all crops.

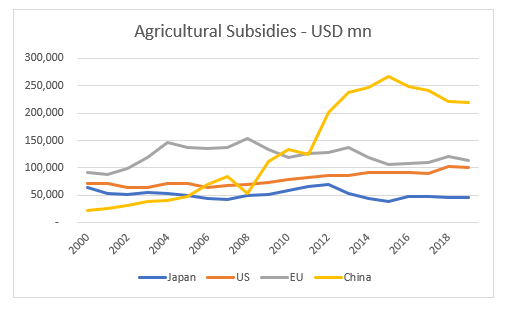

What is even more disturbing about Chinese agricultural production is that growth in recent years has required China to become the world’s largest subsidy payer.

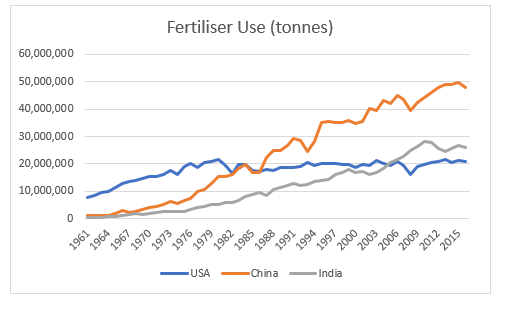

China has also required higher usage of fertiliser to maintain its level of production, even as fertiliser usage has flatlined at other major producers.

If China is struggling to grow food production, then the security of food imports will become paramount. China is a largish importer of wheat, but Russian exports of wheat are much larger than Chinese imports, suggesting this is an area of little concern.

However coarse grain, which is a necessary input for Chinese pig farmers, Russian exports are not sufficient to meet Chinese demand. Only combining Russian and Ukrainian exports can Chinese demand be met. Coarse grain is particularly problematic as the only other large exporters are the US, Brazil and Argentina. That means that Russian and Ukrainian grain exports can be deilvered over land, but other exporters must be shipped, reducing the security in periods of uncertainty.

Thinking about assets from a strategic point of view also offers some explanation to changes in macro markets. For decades the Australian dollar could be relied on to follow the global commodity markets. However in the last couple of years, the Australian dollar has failed to rally, even as its trade surplus has exploded to new all time highs. From a macro perspective it has looked like a buy, but from a strategic perspective, as a political ally to the US, and a commodity supplier to China, its strategic position is vulnerable.

When I originally foresaw a food shock, I expected it to be very problematic for central bankers and bond markets. I am now beginning to see its problematic for geopolitical relations. Investors should consider political implications of their portfolios.